I read an article in Nautilus magazine that combines several topics that interest me and that I have written about elsewhere.

We start back in the 13th century with a young patrician named Ramon Llull in Majorca His story is a bit like Augustine's (who would later become a saint) in that though married, he has many affairs with women and writes songs and poems that no one wants to read - and he doesn't care. Augustine, though he led a lazy, faithless life, reformed through prayer, fasting and alms giving and converts to Christianity.

Ramon found another path from his life of privilege to unexpected divine revelations. In these visions, he was told to write a book that could answer any question about faith. That was quite a task he was assigned.

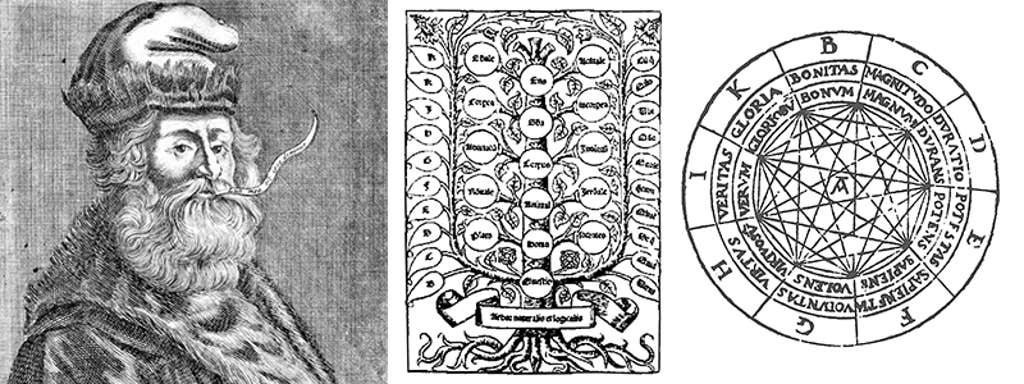

His collected work is known as Ars Magna and it is considered to be more than a book and a kind of logic machine. He was likely partially inspired by the zairja, a device that Muslim astrologers used to help generate new ideas. On a paper wheel, letters and words were distributed around the circumference in a series of concentric circles that could be turned in combinations to "answer" questions

On Llull's paper machine, the wheels were divided into fundamental religious concepts, including goodness, eternity, understanding, and love. You were supposed to rotate the paper discs to combine different divine attributes into logically true statements. It sounds more like a fortune-telling toy than a truth machine, but the article I read says that "his hope to derive truth through the reduction—and mechanical recombination—of knowledge into basic principles and terms prefigured contemporary computing by nearly 800 years."

Although Llull was certain his logic machine would demonstrate the truth of the Bible and gain new Christian converts, he was ultimately unsuccessful. One report has it that he was stoned to death while on a missionary trip to Tunisia.

Ibn Khaldun described zairja as: "a branch of the science of letter magic, practiced among the authorities on letter magic, is the technique of finding out answers from questions by means of connections existing between the letters of the expressions used in the question. They imagine that these connections can form the basis for knowing the future happenings they want to know." (Here is a kind of user's guide to the zairja.)

I like his suggestion that rather than being supernatural it works "from an agreement in the wording of question and answer ... with the help of the technique called the technique of 'breaking down'" (i.e. algebra). By combining number values associated with the letters and categories, new paths of insight and thought are created.

Let's jump to the 17th century and consider the mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz who created a mechanical—but descriptive—logic machine. In Dissertatio de Arte Combinatoria, published in 1666 when he was 19, Leibniz proposed that all concepts could be described as combinations of simpler concepts, in the same way words are composed of letters.

Leibniz knew of Llull’s work but found it incomplete and rather arbitrary. Llull (and by the way, that's a lot of L's in a short name) included goodness, eternity, and love, etc., but why not include others? So, Leibniz suggested the need for a full alphabet of human thought:

Again, God comes into this machine since he hoped this would lead to the language in which God wrote the universe. That would be a universe where no untruth could be spoken.

His thought was also that his “mother of all inventions” would usher in utopia, accelerate science, and perfect theology.

Others preceded him, such as René Descartes, in believing that truth could be discovered through reason alone. And despite critics who questioned all of this, others continued the work of trying to build a truth-generating machine.

English mathematician George Boole had a visionary idea at 17 of how he believed the mind “accumulates knowledge.” Boole was obsessed with the idea of creating a system of language that could put disagreements to rest and calculate truth by mathematical certainty. This led Boole to his 1854 book, Laws of Thought, in which he pioneered a novel form of logic predicated on a new measure of truth: yes or no.

Boole didn't create a physical logic machine, but he developed Boolean algebra, a fundamental concept in binary logic that laid the groundwork for modern computer science. Boolean algebra uses binary values (0 and 1 - kind of yes or no) to represent logical statements and operations, which are essential for designing digital circuits and computer algorithms1.

When I recall algebra - which I never fully understood - the variable I think of is x which stood in for numbers. Boole thought, what if these variables stood for other things, like ideas? He demonstrated that he could turn Aristotle’s logical propositions into mathematical equations.

Do I understand this? No. For example, the proposition “all men are mortal” could be expressed as y=vx. Okay, George, if you say so.

Boole was disappointed that his own work had only captured the interest of mathematicians because he wanted it "to throw light on the nature of the human mind.”

The first logic machine was invented by William Stanley Jevons in 1869. He called it the "logical piano" or "logic piano". This device was designed to solve logical problems using Boolean algebra and was demonstrated at a meeting of the Royal Society of London in 1870.